close

If you have ever gone shopping for wool fabrics you may have seen some of the fabric described as worsted, and some of it described as woolen.

If you are me, you may have wondered what this meant. Aren’t all wool fabrics woolen? I mean, they are wool, right?

Not quite!

In brief, worsted and woolen are different types of wool (long staple vs short staple), prepared in different ways, resulting in a different look and feel. Under magnification, worsted yarns look smooth with long fibres, and woolen yarns are much hairier, with lots of short fibres and more pokey-out bits. Worsted wools are slick when woven, woolen wools are knitted, crocheted, or woven into softer, fluffier fabric, or fulled fabric. Worsted wools are better at keeping out the wind and rain, but woolen wools are warmer, because they are full of air which acts as insulation.

A fluffy woolen wool blanket

Worsted is also used to describe a particular way of spinning yarn, or weight of yarn, but I’m not going to go into that because it’s a modern spinning thing, not a historical textile thing.

Worsted wool comes from sheep with really long wool (long-staple): generally sheep that live in fairly easily accessible, lush, green pastures, as opposed to sheep that do best in harsher environments. The long wool from worsted-type sheep is arranged, either by gilling (pulling through holes) combing with metal combs, or as part of the spinning process, so that the fibres lie parallel and end to end: these long, parallel wool fibres are what characterise worsted wool processing.

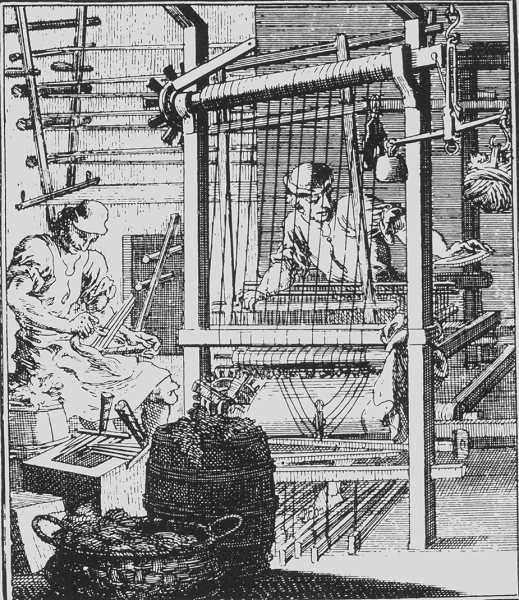

The Weaver (with man combing wool on the left), 1698, Christoph Weigel

Because worsted wool is made from long fibres which all lie parallel, the natural crimp of the wool is removed, and the forms a very tight, hard yarn when spun, with little space between the fibres (as opposed to the more open, fluffy woollen yarn). When woven into fabric, worsted fabric has a tighter, harder, shiny-er finish, and can make a finer, lighter weight fabric.

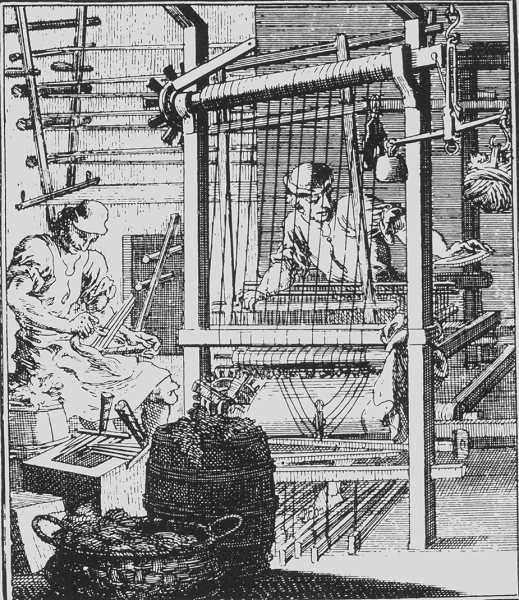

Here are two different worsted wools, so you can see how slick and hard the finish is, with few wool hairs on the surface. The dark blue fabric is a serge, the camel a cavalry twill.

The development of worsted wool fabric (in the modern sense) dates back to the Middle Ages, when changing agricultural practices in England meant that new breeds of sheep that thrived on rich, enclosed pastures were being introduced, at the expense of older breeds, which did better in rougher environments. At the same time waves of Flemish weavers, fleeing unrest in the Low Countries in the early 14th century, immigrated to Norfolk in England in response to invitations to settle in England offered in 1271 to fullers, dyers and weavers. They set up weaving in and around Worstead, in Norfolk, and introduced new spinning and weaving techniques. The type of cloth they produced came to be known as worsted.

Worsted cloth was known in the 18th and through the 19th century as stuff to differentiate it from cloth, which was woollen fabric. Stuff was also used to describe other woven fabrics of fibres other than silk, especially once cotton became more common as a fabric in the late 18th century, so a mention of a garment made of stuff does not necessarily mean the item was made of wool, simply that if it was, it wasn’t woollen.

Worsted wool fabric tends to be more expensive than the same weight and quality of woollen fabric, because the pasture land needed for worsted sheep varieties is in higher demand (in New Zealand, for example, it is far more financially beneficial for farmers to use pasture land for dairy cows than wool sheep), and because worsted fabrics require more processing. However, you also get more wear for your dollar: worsted fabrics are also more durable than their woollen counterparts. Desirable light or ‘tropical’ weight wools are generally worsted as well.

The one drawback, wear-wise, to some worsted fabrics is that they may go shiny at areas that receive a lot of wear, such as the seat of pants and skirts, as the parallel fibres are pressed more firmly together. Twill weaves are more likely to go shiny than plain weaves.

There is also a semi-worsted type of fabric, with yarns that are spun tightly, but not combed. This is a cheaper process, and is usually done with inferior wool to further cut costs. Even with 100% wool fabrics there can be huge differences in quality and durability, which is why I prefer to buy fabric, and wool in particular, in person rather than online, unless it is from a very reputable supplier.

Today, worsted fabrics are most likely to be seen in men’s suiting, and in trench coats and other outerwear.

Woolen wool usually comes from sheep with shorter wool fibres, though the shorter fibres (under 8cm/3″ or so) of long-staple sheep varieties that are combed out in the worsting process can also be used to make woollen cloth.

To make all the short bits of woollen wool lie nicely together so that it can be spun into yarn, it is carded, or brushed in two directions at once with stiff brushes. The name carding comes from the Latin carduus or teasel, because carding was originally said to have been done with teasel heads (note, the use of actual teasels for the initial carding is under some debate).

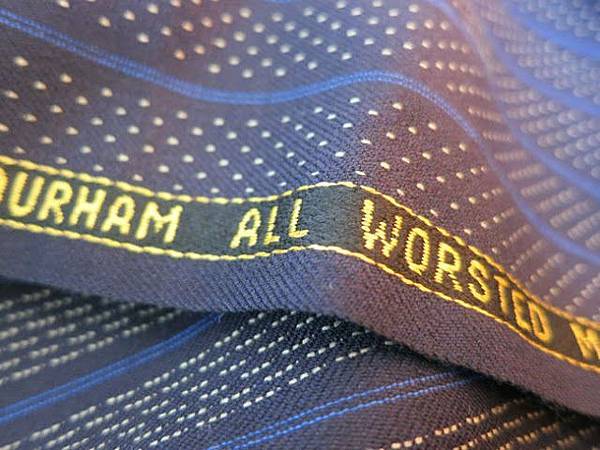

Giovanni Boccaccio, De mulieribus claris (On Famous Women), 1374, illustration showing women spinning, carding, combing, and weaving wool

Once it is carded, the wool is spun, and then woven. After weaving, woolen cloth is sometimes subjected to the fulling process (also known as waulking or tucking), which cleans the fabric, making it thicker, and works the hairs of the wool together, creating a uniform, almost felted surface, without much visible weave. Fulling basically involves pounding or rubbing the surface of the cloth, either with hands, feet, or clubs, or in special water-driven fulling mills, which began appearing in England in the early Middle Ages.

The first part of the fulling process is scouring, when cleaning agents were pounded in to the fabric. These agents were initially urine (the Romans used it), which is full of ammonia, which softened and whitened the wool, and later fullers earth, clay with mineral elements which performed the same purpose of softening, whitening, and absorbing oil and dirt. Fullers earth is sometimes known as bleaching clay.

Once the wool was scoured, it would be rinsed (thoroughly!), and then beaten again, to matt the fibres together and thicken the cloth, making it more water and wind resistant.

Woolen cloth can also be brushed with teasels or carding combs after it is woven, to raise the nap of a fulled surface. This too was done with teasel heads: in fact, there are still some wool processing plants that still use teasel heads set on to a special frame for the initial or post-wearing carding. There is at least one teasel-head carding frame still in use in a commercial factory in New Zealand – which I think is pretty awesome.

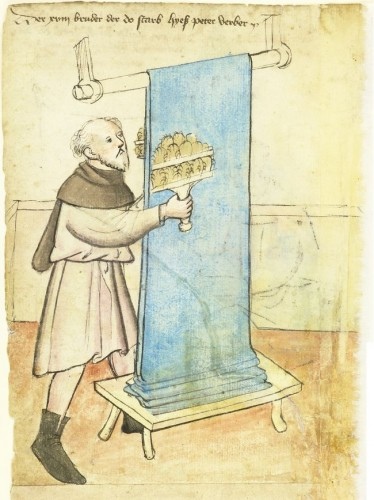

Mendel Hausbuch, f. 6v, c. 1425, Peter Berber, Carder brushing woollen cloth with teasel heads

When woven up, woolen cloth is usually softer and fluffier than worsted stuff, though it can also be pricklier and hairier, if made with cheaper wool. It’s generally easier to fit and sew with, because it isn’t as slippery and stiff as worsted, and woolen cloth gives and eases around your body more. However, certain woollen weaves are prone to snagging, and may sag at the knees and bottom, or wear out at the knees.

Have a piece of fabric and want to know if it is worsted or woolen? If it is soft and fluffy, or has a brushed, fulled surface that looks almost like felt and makes it hard to see the weave, it’s woollen. If it has a smooth, slick, hard surface, it’s worsted.

The soft, open woolen weave of my Roman stola

Worsted fabrics generally look best for suits, and other smart, crisp, tailored garments. Woolens are softer looking and drape better, so work better for more informal garments.

Common modern & historical woolen fabrics include:

- Boiled wool – woolen fabric, woven or knit, which has been thickened or shrunk by heavy fulling and/or boiling. You can create your own boiled wool by washing your fabrics multiple times on the hottest, roughest setting – assume that you will loose approximately 20cm of length for every metre.

- Boucle – fabrics of wool or other fibres with twisted, irregular crepe threads and a loopy, textured weave.

- Camelet – medium quality woolen fabric produced in England in the Middle Ages.

- Camelin – luxury woolen cloth made from the wool of the angora goat, imported into England from the Near East in the Middle Ages.

- Challis – soft, draping, lightweight, plain weave fabric of wool, cotton, or rayon.

- Crepe – soft, draping fabric with a twisted thread, giving it a slightly nubbly surface and excellent drape, recovery, and movement around the body. Wool crepes can range from very lightweight, to heavy double-weave crepes.

- Knits (jersey, doubleknit, etc)

- Tweeds – woolen cloth with an unfulled surface, often with mixed (heathered) yarns.

Common modern & historical worsted fabrics include:

- Barathea – very fine twill weave fabric, mainly used for mens dress suits.

- Bombazine – a twilled or corded fabric with a silk warp and worsted weft (now sometimes all silk, or made of other fibres).

- Cavalry Twill – a fabric with a steeply diagonal twill weave, and a distinctive raised ‘cord’ or rib. Also known as artillery tweed.

- Gabardine – A very tightly woven fabric with a fine steeply diagonal warp faced (has a clear wrong and right sides) twill weave, invented in 1879 by Thomas Burberry, originally as a kind of waterproof fabrics, but used as a general term for the weave and fabric type by the early 20th century. The name is taken from ‘gaberdine’, a word for cloak or raincoat dating back to the late Middle Ages.

- Serge – Very tight, hard wearing twill weave, frequently used for suiting, but prone to shining.

- Sharkskin – lightweight wool fabric with a fine, nubbly weave that is supposed to imitate the skin of a shark.

- Whipcord – like cavalry twill, a fabric with a steeply diagonal twill, and a raised ‘cord’ or rib. There is no official difference between whipcord and cavalry twill (except that whipcord may also be made of cotton), so either term may be used to describe certain fabrics.

For further posts on fabric, check out my post on the difference between brocade and jacquard (and all those other weaves that can be achieved with a jacquard loom), and the difference between voile, lawn and muslin, as well as all the posts through The Historical Textile & Fashion Encyclopedia.

Sources:

Cant, Jennifer and Fritz, Anne, Consumer Textiles. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. 1988

Calasibetta, C. M., Tortora, P, and Abling, B (illus.). The Fairchild Dictionary of Fashion(Third Ed). London: Laurence King Publishing Ltd. 2003

Collier, Billie J. and Tortora, Phyllis G. Understanding Textiles (Sixth ed). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall Inc. 2001

Ginsburg, Madeleine (ed), The Illustrated History of Textiles. New York, New York: Portland House. 1991

James, John. History of the Worsted Manufacture in England. London: Frank Cass & Company, Limited. 1968

Shaeffer, Claire. Claire Shaeffer’s Fabric Sewing Guide. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. 2008

Wilard, Dana. The Fabric Selector. Millers Point, NSW Australia: Murdoch Books Pty Ltd. 2012

文章標籤

全站熱搜

留言列表

留言列表